Breakfast is not real and breakfast skippers do not exist

- Asker Jeukendrup

- May 3, 2020

- 4 min read

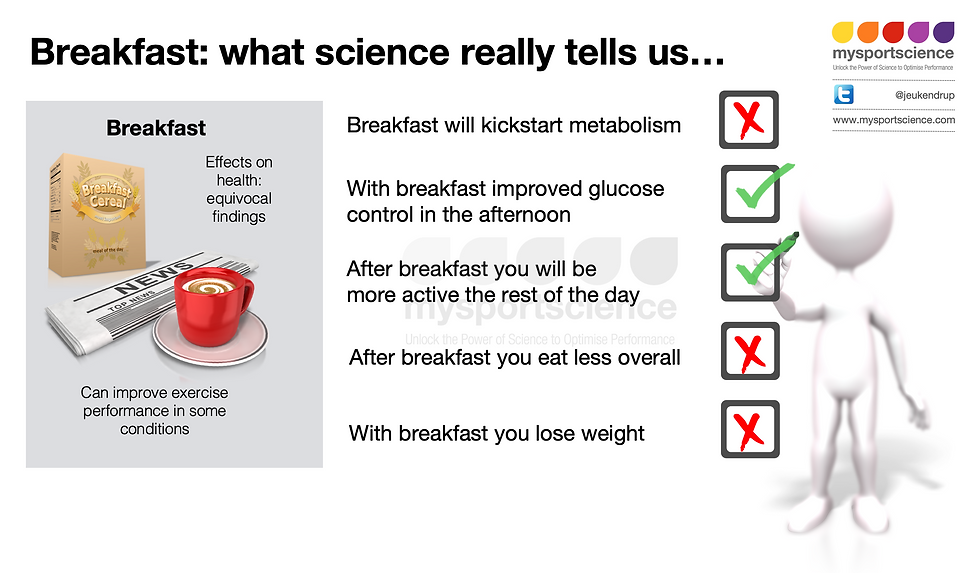

The seemingly mythical status of breakfast stems from age-old tales of reduced appetite later in the day and legendary feats such as ‘kick-starting metabolism’ to avoid ‘starvation mode’, all leading to that holy grail of dieting: to lose weight while eating whatever you like (not to mention rumours of improved cognitive and physical performance along the way). Like most mythical tales, however, these accounts are only partly grounded in the truth and there is no such thing as breakfast.

What is a breakfast?

Defining ‘breakfast’ is notoriously difficult and we do not all have a shared understanding of what it actually is (see this paper for a detailed discussion). Opinions are often therefore divided about what constitutes this thing called breakfast, so it is difficult to know whether someone has eaten it. Even just considering morning meals typical to Westernised cultures alone, which many people might agree are ‘breakfast foods’ (e.g. a high-fibre/low-sugar cereal, pancakes with maple syrup or a ‘full-English’); we would not expect similar acute metabolic responses or chronic health outcomes when ingesting such nutritionally diverse foods. These complexities in defining breakfast are relevant because we are repeatedly presented with the overly simplified concepts that breakfasts in general may or may not be important and, moreover, that two physiologically distinct categories of humans exist: breakfast consumers versus breakfast skippers. The concept of chronotype certainly has empirical support (whereby one individual may be more of a morning-type than another), yet the reality is that breakfast habits are neither a binary variable nor a stable trait. A person cannot therefore be reliably classified as a ‘breakfast skipper’ because that would depend entirely on the definition employed and time-scale in question.

Mainstream media confusion

The over-simplification of breakfast in the mainstream media has made it almost impossible to decipher consistent public health messages on this topic. Individuals trying to make an informed decision about whether to consume breakfast might then be forgiven for any confusion when considering the range of headlines in recent years (even the same news outlet can publish two utterly contradictory reports within a matter of weeks - about the same original scientific paper!).

Do we know enough?

Is further research required before any evidence-based conclusions can be drawn? More data would certainly be helpful but current understanding is nonetheless at a stage where several effects of breakfast have now been established. Regarding the question of whether breakfast makes us eat less later in the day, it has in fact been verified using various levels of evidence and across a range of experimental designs that total daily energy intake is more likely to be lower if we skip breakfast. This has been a reasonably consistent finding using cross-sectional diet surveys, laboratory-based meal tests and randomised controlled trials under free-living conditions.

Does eating less mean weight loss?

Some people may then immediately assume that eating less overall is a good thing based on the (false) expectation that weight-loss will necessarily follow, so argue against consuming breakfast. Conversely, others may be puzzled that people who report skipping breakfast tend to eat less overall given that cross-sectional studies clearly show regular morning fasting is actually associated with being moreoverweight. In addition, randomised controlled trials have not revealed any effect on body weight irrespective of whether or not the overnight fast remains unbroken until the afternoon.

Whilst it might at first seem paradoxical that morning fasting can reduce daily energy intake without resulting in weight loss, this merely indicates that compensatory reductions in metabolic requirements must occur to offset any energy deficit. Despite the common belief that this is achieved via a slower baseline level of metabolism day-to-day when not regularly consuming breakfast, the available evidence does not support this view as resting metabolic rate is quite stable in the absence of weight change and so remains predictable based simply on body mass. Instead, a more likely explanation emerging from recent trials is that the compensatory response to prevent weight-loss with fasting is achieved by limiting the energy expended above resting metabolism via lower engagement in spontaneous low-level physical activities (i.e. movement).

Don't forget physical activity

One interpretation of the above pattern of results is that skipping breakfast is ineffective for weight-loss because the attained level of caloric restriction is directly undermined by lower physical activity (especially considering that a sedentary lifestyle is an independent risk factor for chronic disease). However, unlike if the compensatory response to fasting had involved a slower resting metabolic rate (i.e. adaptive thermogenesis), the apparent behavioural response is thankfully under a degree of conscious control. Therefore, although you cannot be certain whether what you eat each morning truly qualifies as breakfast or whether you then fit the nominal category of a habitual consumer, we can recognise our increased natural propensity for sedentary behaviour prior to breaking the overnight fast and so actively seek opportunities for greater engagement in physical activity.

References

Betts JA, Chowdhury EA, Gonzalez JT, Richardson JD, Tsintzas K, Thompson D. Is breakfast the most important meal of the day?Proc Nutr Soc. 2016 Nov;75(4):464-474.

Read more on breakfast here: Is breakfast the most important meal of the day?

Comments