Mental fatigue in sport- what is it and how do we recover from it?

- Asker Jeukendrup

- May 3, 2020

- 4 min read

Most of us are familiar with the term fatigue; especially as it relates to exercise. We understand how it feels and the consequences it has on how we perform. There is a significant amount of scientific literature on fatigue as a result of exercise and while often debated, much is known about the mechanisms of fatigue. Mental fatigue, however, is an area of sport science where much less is known, yet has been gaining increasing attention. Mental fatigue is defined as a psychobiological state caused by prolonged periods of demanding cognitive activity (1, 3); indicated by increased subjective feelings of mental fatigue, decreased cognitive performance and physiological changes, following prolonged, challenging cognitive tasks (7).

"Drained"

An athlete may describe feeling both physically fatigued as well as mentally ‘drained’. Alternatively, an athlete may feel they have recovered adequately from a physical perspective, however due to stress, travel or cognitive load, feel that they are not mentally recovered.

Mental fatigue itself has been shown to impair aspects of exercise performance and participating in elite team sport may be particularly demanding from a cognitive perspective (7). However, despite elite athletes and staff perceiving mental fatigue to hold a negative impact, some research has suggested that elite athletes may be more resistant to mental fatigue due to experience and/or training (5).

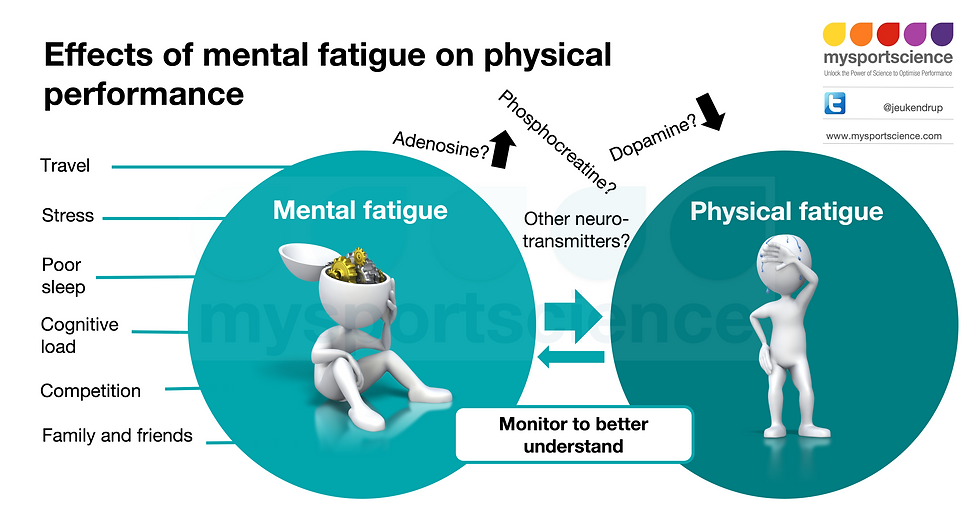

Mental fatigue may influence physical performance

Regardless, given many athletes are exposed to significant cognitive and emotional load (i.e. social media, sponsorship, selection, injury concerns) as well as poor sleep, long-haul travel and high training loads. It is reasonable to suggest that managing mental fatigue is of importance for athletes and also for individuals who combine long working hours and high training loads. Some research suggests that mental fatigue has the potential to negatively affect performance through not only a reduction physical performance, but also as a result of change in technique, decision-making and tactical and skill execution (7).

Mechanism

The negative influence on physical performance has largely been attributed to an increased perception of effort; proposed to be a result of adenosine accumulation and decreased dopamine concentrations in the brain (4). However, the exact mechanisms responsible for mental fatigue are yet to be confirmed with creatine, glucose, and various other neurotransmitters, also likely to play a role (6, 8).

Monitoring

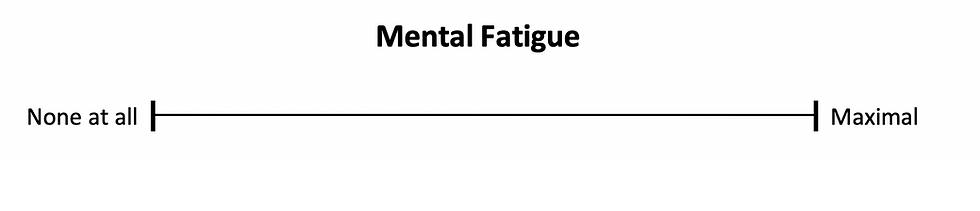

Many coaches describe how training quality is reduced when, for example, athletes are undergoing exams or high periods of stress. Monitoring the outcome of this via an assessment of mental fatigue may be important when periodising and planning training. A simple visual analogue scale (VAS) can give coaches and staff an increased understanding of the degree of mental fatigue an athlete is experiencing. This can be as straightforward as the figure below, a 100-mm horizonal line anchored from “none at all” (0) to “maximal” (100). Practically however, concurrent assessment of perceived physical fatigue is advised, along with recommendations to provide a clear, sports specific definition of mental fatigue and familiarisation to ensure athletes fully understand the terminology and purpose of assessment.

Figure 1: Example 100mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) that can be used to monitor mental fatigue regularly.

As research in mental fatigue is minimal, we know very little about the underlying mechanisms of this type of fatigue and also how to best recover when mentally fatigued. At a minimum it is likely important that we consider how high levels of mental fatigue may influence performance and begin to measure and manage this more effectively.

Are there nutrition solutions?

Some nutrition-based suggestions to acutely reduce mental fatigue from the literature include: caffeine, a caffeine-maltodextrin mouth rinse, creatine supplementation and glucose administration, however these are yet to be tested in research studies in athletes (7). Sleep monitoring and education to enhance sleep, managing travel schedules, minimising Smartphone (2) and computer game use as well as experimenting with relaxation strategies may be useful ways to recover from high levels of mental fatigue and ultimately enhance performance.

References

1. Desmond P and Hancock P. Active and passive fatigue states. In: Stress, workload, and fatigue edited by Hancock P. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2001, p. 455-465.

2. Greco G, Tambolini R, Ambruosi P, and Fischetti F. Negative effects of smartphone use on physical and technical performance of young footballers. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 17: 2495-2501, 2017.

3. Job R and Dalziel J. Defining fatigue as a condition of the organism and distinguishing it from habituation, adaptation, and boredom. In: Stress, workload, and fatigue edited by Hancock PA. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2001.

4. Martin K, Meeusen R, Thompson KG, Keegan R, and Rattray B. Mental fatigue impairs endurance performance: A physiological explanation. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ): 1-11, 2018.

5. Martin K, Staiano W, Menaspa P, Hennessey T, Marcora S, Keegan R, Thompson KG, Martin D, Halson S, and Rattray B. Superior Inhibitory Control and Resistance to Mental Fatigue in Professional Road Cyclists. PloS one 11: e0159907, 2016.

6. Meeusen R and Roelands B. Fatigue: Is it all neurochemistry? European Journal of Sport Science: 1-10, 2017.

7. Russell S, Jenkins D, Smith M, Halson S, and Kelly V. The application of mental fatigue research to elite team sport performance: New perspectives. J Sci Med Sport 22: 723-728, 2019.

8. Van Cutsem J, Roelands B, Pluym B, Tassigno B, Verschueren J, De Pauw K, and Meeusen R. Can Creatine Combat the Mental Fatigue-associated Decrease in Visuomotor Skills? Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 2019.

Comments